|

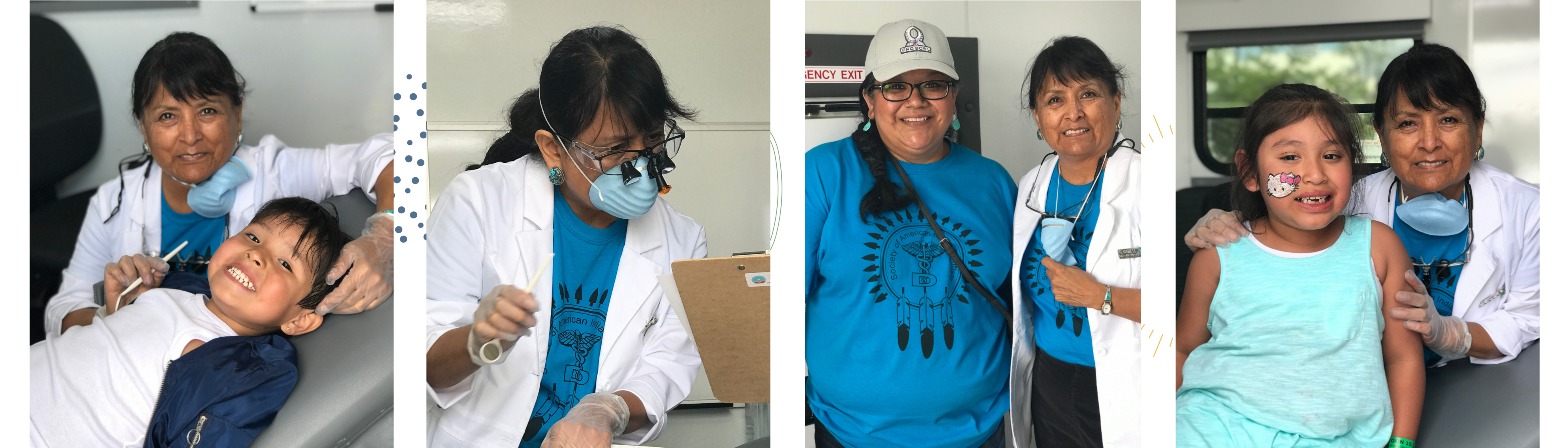

2024 Hall of Fame Awardee: Darlene A. Sorrell, DMD

Written by Byron Voirin

Darlene was born at Fort Defiance on the Dine’Nation. She is Red House, (Kinlichiinii) , clan born for Where Waters Flow Together, (To’ aheedliinii), clan. She is the 7th of 9 children, having four brothers and four sisters. Many of her childhood memories were created in Sheep Springs, Crystal, and Tsaile where her parents grew up on the Nation.

She says that at age 10 she decided to be a dentist. Perhaps this correlated to her desire to have braces, which was seemingly impossible in a family of her size. Ah, but you know her determination to make things happen. She calculated the cost of braces in a town 45 miles from Morenci, Arizona where her father had secured a job in the copper mines. She ironed her teacher's clothes, cleaned houses, and saved summer job money. Her sisters would drive her to the orthodontic appointments though her parents never went. She finally paid off the braces from her own efforts. Imagine how many of today’s permission and HIPPA codes were violated, and how a native girl not old enough to drive could convince a clinic she could pay!

In Morenci, her family lived in a two-bedroom company house located in “Tent City”, where all the Native American families were segregated to live. It was the only neighborhood without bus service to the schools until her eldest brother became student body president and forced the issue leading to a district policy change.

Darlene’s father did not speak English. As her senior year at Morenci was to start, a life-changing event occurred. Her father lost his leg in a mine accident. Recall they rented a company home so after a couple of weeks the company asked them to vacate. Darlene was on track to become the valedictorian so the teachers at the company school petitioned to allow them to stay so she could complete her senior year. There was never a formal agreement but as time went on she continued her studies and became the salutatorian. They left Morenci the day after the graduation ceremony.

Many of her siblings had laid the path for her to follow to the University of Arizona where she majored in Medical Technology. At one point there were 7 of her siblings all enrolled at Arizona at the same time. A vivid memory she has is discussing leaving for college with her mother. Her mother was a soft-spoken woman who advised her, “they, ( the majority population), think they are better than you. BUT THEY ARE NOT.”

As her undergrad years were ending she applied for dental school. Arizona had no school at that time so she applied for UCLA, USC, Washington, Pacific, and Oregon. The first acceptance letter she received was from Oregon and she immediately accepted. She was accepted at all of them eventually. At the time, she was unaware that she was the first person from the Dine’ Nation to gain acceptance to Dental School. During this time Dr. Bluespruce and the handful of native dentists that existed formulated this organization you are part of today and that is where Darlene and these others founded the American Indian Dental Society in the early 80’s. Unfortunately, as the late 80’s and early 90’s saw the rise of HIV, the acronym of the original name needed to change, thus SAID came to be.

After finishing dental school, Darlene desired a position in one of the numerous the Navajo Nation clinics. Indian preference had become law and there were some within the IHS system that resented it. Washington said there were no openings on the entire Navajo reservation. That had to be the first and only time that has occurred. Instead, she was offered the Hopi Reservation. No problem, except the Hopi/Navajo land dispute was at its height. 1200 Navajos families and 50 Hopi families were being forced to relocate from their homes back onto their newly drawn reservations or into border towns. Despite high tensions in the disputed land areas, confiscation of livestock and some violence and gunplay between the tribes, it did not carry over into the clinic.

Compounding the problems though, an issue between the female chief dentist and a staff dentist resulted in his arrest and her requesting an immediate transfer. There was only Dr. Sorrell, fresh out of dental school, to inherit the chief’s position. On Hopi, she finally relented after a 10-year relationship and married her husband Byron, the Mental Health Specialist for the Hopi Tribe. They had met at the University of Arizona and wed at the hogan in Crystal, having a traditional Navajo wedding. He gave her family a bull, two cows, three sheep, Bisbee turquoise, deer hides, 50 bags of flour, and several hay bales. The deal was done and his mother, keeping with tradition, still has their wedding basket.

At this time in history a commissioned officer, which Darlene was, had to move to be promoted. Our adventuresome souls took over and we inquired about Alaska. The result was Dr. Sorrell becoming the chief of the SEALASKA native corporation clinic in Juneau. On her first day she met a retired Dine’ nurse who helped triage incoming health patients, Ida James. Ida cried when she met Darlene saying she never knew if she would see a Dine’ doctor or dentist. Coincidentally, she wound up being Darlene’s father’s cousin.

Darlene would do remote village work, flying into a village, working 10-13 hours for two days, and sleeping on floors of gyms or clinics in sleeping bags, until everyone was helped. She recalls that on one flight, the weather closed in on the small plane, and the pilot, who you sometimes sat next to, was scared but he skillfully found a way to get them down safely.

After three years in Juneau, she was accepted to the advanced general practice residency in Anchorage. She developed her skills further with one teacher there declaring she had the best working dental hands he had ever seen. She was assigned the Aleutian Chain clinics, flying as far as Dutch Harbor and serving villages on Kodiak Island, Larson Bay on Kodiak, she sat in a pick-up truck as a Kodiak Brown Bear peered at her through the passenger window. At Dutch Harbor, she once treated a Russian fishing sailor for an emergency toothache. He said he was thrilled about the use of anesthetic, something that was uncommon in his homeland.

When her residency ended, Dr. Sorrell applied to be the Clinical Chief of Albuquerque Area Clinic at SIPI. The practitioners in Alaska had all been welcoming and encouraging and treated Darlene as a colleague. However, that was not the case for this new position. After a curious 7-month delay Dr. Sorrell learned that not all colleagues would be as collegial as those in Alaska. Ultimately, after seeking council for EEO, the hiring supervisor was dismissed. She was not the first woman he attempted to run off, but she was his last.

As tribes began to contract their dental money away from SIPI a few years later, the clinic dwindled to Dr. Sorrel and three assistants. With the help of New Mexico’s US Congresswoman Heather Wilson, $500,000/year for the SIPI clinic was secured. Community action groups were instrumental in helping but Dr. Sorrell knew the clinic would not survive on that amount alone. She proposed and sold a radical idea that only patients 18 and younger would be seen along with up to 5 emergency patients daily. This would maximize Medicaid and perhaps they could continue. SIPI did not just survive, it thrived with parents happy to have children prioritized. As the clinic grew to 26 chairs, the maximum patient age was pushed first to 25 and then age 30.

From that first clinic on Hopi to SIPI she offered to mentor students of all backgrounds. She has been extremely satisfied to hire some of those she mentored. She is thrilled to see the ever-increasing number of native dentists.

Dr. Sorrell has visited all 50 states, every continent but Antarctica, numerous countries, and watched her son play on American basketball teams in France, Switzerland, New Zealand and Australia. Chase, A wildlife biologist lives in Tucson with his daughter, Nizhoni.

Darlene once held resentment towards America because of the state of Native Nations within its borders. Absolutely she still believes she is a member of the out-of-sight, out mind people in this country. At the same time, she feels fortunate to be American after seeing so many other countries with so much less. She believes strongly that we need to take care of our own and she hopes that our next generations of native dentists will find ways to provide that care and teach our people how to improve their own dental health.

|